Oh no, not I, I will survive

Oh, as long as I know how to love, I know I'll stay alive

I've got all my life to live

And I've got all my love to give and I'll survive

I will survive, hey, hey

I Will Survive (1978) by Gloria Gaynor

Every time I hear “survival”, this song pops up in my mind. There’s an important phrase here: as long as. We tend to promise ourself to survive (i.e. keep doing the same thing) as long as certain criterias are met. If the criterias are met, how certain are we that we could survive? I have a simple case related to surviving - the notebook can be accessed here.

On weekdays, I commute to Jakarta using either train or TransJakarta. Since those are public transportations, we can’t expect the vehicle has enough space for all passengers (yes, I don’t even mention comfortable). Thus, sometimes I have to wait for the next train or bus, wishing that there is more space to get in. The question is, will the vehicle be spacious enough so that I could get in? Usually, I will keep waiting as long as I haven’t waited for more than 30 minutes - but I might wait longer. If that’s the case, how likely will I get in the bus after waiting for t minutes? This kind of problem can be approached using survival analysis. Wait.. what?

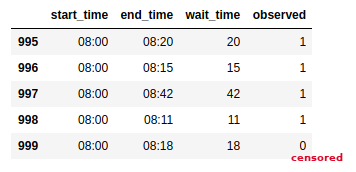

Just like its name, survival analysis is analyzing the state or fact of continuing to live or exist, typically in spite of an accident, ordeal, or difficult circumstances. In this case, the difficult situation is getting in the bus. Let’s say we have a dataset of bus waiting time and the observed outcome: get in a bus or unknown. Yes, it can be unknown, since we might not know the final outcome yet at the time of data collection. For example, I haven’t got in the bus after waiting for 18 minutes, and we don’t know whether I continue waiting until I get in the bus or decide to use other means of transportation. We call this censorship.

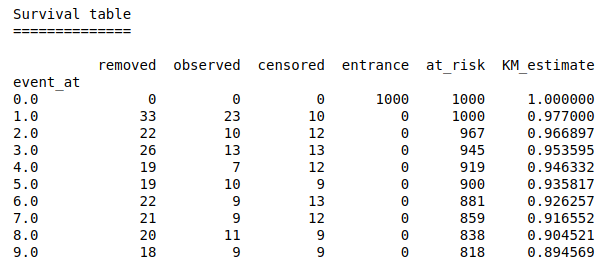

We aggregate the dataset based on the waiting time, and calculate how many times I get in the bus (observed - or death), and how many times the final outcome is unknown. Then, we calculate the survival function S(t) = Pr(T>t); which describes probability of surviving past through time t. Since the observed event on our case is “getting in the bus”, then the survival function calculates probability of not getting in the bus at time t. It can be calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimator. Simply put, we calculate product of survival probability up to time t (see KM_estimate on Figure 2).

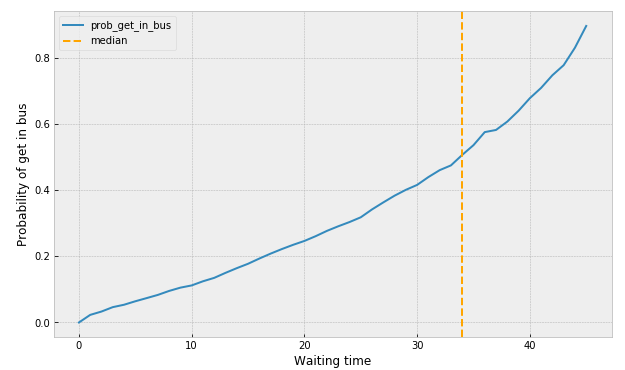

To make it more intuitive, we plot 1-KM_estimate: probability of getting in the bus (see Figure 3). Based on the calculation, I am more likely to get in the bus after waiting for 34 minutes. Wow, it surely is crowded at the city, eh? Given this result, we could suggest to add more buses, so that passengers don’t have to wait for such a long time.

Conclusions

There are a lot of applications of survival analysis, e.g. subscription to a service, repeat purchase behavior, recovery after being sick. Application of survival analysis on marketing, for example, can suggest on what time the company should re-engage with the customers so that they keep using the service.

While this analysis uses 1-KM estimate, we could also use Nelson-Aalen fitter to estimate probability of having observed event (in this case: probability of getting in the bus) using hazard function. We usually use Kaplan-Meier estimate on calculating survival probability, whereas Nelson-Aalen fitter focuses on calculating probability of death event. I haven’t figured out further about Nelson-Aalen fitter, but it is said that the hazard curve is the basis of more advanced techniques in survival analysis.

References

[1] Lifelines - Estimating the survival function using Kaplan-Meier